by Peter Stone and Ellen Harold

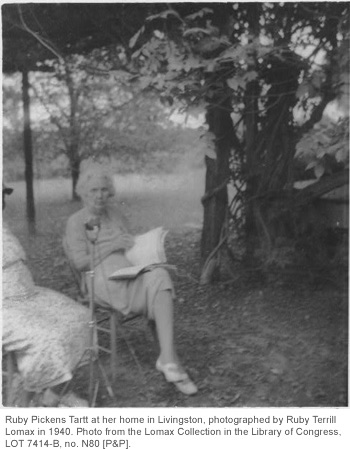

Ruby Pickens Tartt (1880–1974) of Livingston, in Sumter County, Alabama, was an avid collector of local folk songs and folklore, much of it African American, as well as an artist and craftswoman. So renowned were her folk collecting activities that, even before she met John A. Lomax in 1936, her home had become a mecca for writers and folklorists. A celebrated raconteur and hostess, Mrs. Tartt delighted in organizing excursions, parties, and picnics. Local singers, whose friendship she had carefully cultivated, provided the entertainment for her guests. These included (in addition to the senior Lomaxes) Carl Carmer, Julia Peterkin, Doris Ullman, and, in the late thirties and forties, Alan and Elizabeth Lomax, Harold Courlander, and Elie Stiegmeister, whose Music Lover’s Handbook, 1943, includes an account of his visit to Livingston.

She was born Ruby Stuart Pickens on January 13, 1880, the daughter of Fannie West Short and William King Pickens, a wealthy cotton planter. Like the other leading families of the Sumter County, the Pickenses prided themselves in being people of some cultivation. Livingston, the County seat, had been founded in 1832 by planters from Virginia who came to Alabama’s Black Belt (so named for the fertility of its soil) when the region was opened up to cotton planting after the removal of the Choctaw Indians. Somewhat unusually for a frontier town, from its beginnings Livingston had a boy’s school and a girl’s academy, and it soon boasted a public library.

Ruby’s maternal grandmother, Mary Champ, was a remarkable and artistic woman. Left a widow with five children in 1861, she made a career for herself as an educator, first opening a small school in her house and then becoming assistant principal of the Livingston Female Academy. Herself a talented painter, she gave her daughter Fannie the middle name “West” after American painter Benjamin West and persuaded Fannie to similarly name her granddaughter Ruby “Stuart” after Gilbert Stuart (George Washington’s portraitist). As a small child, Ruby learned to draw under her grandmother’s tutelage. She then attended the Livingston Female Academy, later successively called the Alabama Normal School, Livingston State Teachers College, Livingston University and now the University of Western Alabama. In 1899 Ruby studied art and English at Sophie Newcomb College, Tulane University, and then traveled to New York City to study portraiture with the impressionist William Merritt Chase at his School of Art and photography with Arnold Genthe, renowned for his photos of San Francisco before and after the 1906 earthquake. While in New York Ruby was so enthusiastic about plays, operas, and museums that her father observed that though he was paying for her to study art, “she seemed to be attending everything the curtain went up on instead.” However, at the end of the year she returned to Livingston to teach and eventually to head the Art Department at Livingston Female Academy.

Ruby’s maternal grandmother, Mary Champ, was a remarkable and artistic woman. Left a widow with five children in 1861, she made a career for herself as an educator, first opening a small school in her house and then becoming assistant principal of the Livingston Female Academy. Herself a talented painter, she gave her daughter Fannie the middle name “West” after American painter Benjamin West and persuaded Fannie to similarly name her granddaughter Ruby “Stuart” after Gilbert Stuart (George Washington’s portraitist). As a small child, Ruby learned to draw under her grandmother’s tutelage. She then attended the Livingston Female Academy, later successively called the Alabama Normal School, Livingston State Teachers College, Livingston University and now the University of Western Alabama. In 1899 Ruby studied art and English at Sophie Newcomb College, Tulane University, and then traveled to New York City to study portraiture with the impressionist William Merritt Chase at his School of Art and photography with Arnold Genthe, renowned for his photos of San Francisco before and after the 1906 earthquake. While in New York Ruby was so enthusiastic about plays, operas, and museums that her father observed that though he was paying for her to study art, “she seemed to be attending everything the curtain went up on instead.” However, at the end of the year she returned to Livingston to teach and eventually to head the Art Department at Livingston Female Academy.

After her marriage on October 18, 1904, to her childhood sweetheart, William Pratt Tartt, a local banker, Ruby gave up teaching and became active in community affairs. On June 21, 1906, she gave birth to their only child, Fannie Pickens Tartt (Ingliss), who herself would become a portraitist.

The Pickenses, like other old families of Livingston, took an active interest in their black tenants, knowing them each by name, attending their funerals, and the like —with attitudes that, from our historical perspective, can best be called “benign paternalism.” After the Civil War, former slaves lived on small plots of land subdivided from large plantations and rented from white owners who claimed a share of the crops, an arrangement perpetuated into the 1950s. Growing up, Ruby Pickens loved to accompany her father in his buggy — which she, already temperamentally independent, insisted on driving herself — as he visited his black tenant farmers in the country. Thus began her engagement with the talent and beauty of black folk culture, engendered by her father’s own appreciation of it. Outwardly, at least, the blacks accepted the system and reciprocated the good will of the Pickens family. It was on such an outing, to a black religious service, that father and daughter first heard the singing of Doc Reed, “ whose rich voice sounded out from the group like a trumpet call” (see: Virginia Pounds Brown and Laurella Owens, Toting the Lead Row: Ruby Pickens Tartt, Alabama Folklorist, University of Alabama Press, 1981, p. 18).

Born into privilege and the planter class, Ruby Tartt had the executive ability and manner of an ante-bellum and Reconstruction “boss lady” who expected to be deferred to. She used these abilities, however, to try to influence local lawyers to give legal help to the black population. It upset her that the black section of town lacked fire protection and that black people were not allowed to sit on benches in the public square or to use the public restrooms. As an artist she also deeply appreciated the richness, beauty, and importance of the black cultural heritage. She even preferred to listen to the music at black churches to attending the one she was brought up in. Equipped with pen, paper, easel, and paints, alone or with friends, she explored by auto (one of the first in the state, given her by her father) the isolated rural black communities of Alabama in search of songs, field calls, games, stories, superstitions, and folkways, listening to the people while sketching and painting them and their environments, in the hope that they would not sink into oblivion. That she was often the subject of gossip in a group of people, not to mention being the proximate and prime cause of its sudden silence, seemed not to faze her. “Come to think of it,” she mused in the nursing home where she lived in her late years, “I was nearly always alone in the enjoyment of my various interests. Therefore, I was ‘nuts’ according to public opinion — and to think I’m still, at ninety, running true to form.”

In 1926 New York writer and Harvard graduate Carl Carmer (1893–1976) was appointed Professor of English at the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa. While chaperoning its drama club for a performance in Livingston, he stayed with the Pickenses. He and Ruby became friends and he would return often. He reminisced how, when talking to her, “I was drenched in a shower of proverbs, spells, superstitions, recipes, descriptions of all-day-singings-with-dinner-on-the-grounds, county barbecues, fiddlers conventions, ballads of old crimes, tales of Bre’er Rabbit and Sis Cow, baptizings, spirituals, [and] poetic quotations from Negro preachers” (Carl Carmer, Miss Ruby, My Most Unforgettable Character, Livingston, Alabama: Livingston University Press, 1975, p. 3). When he told her he planned to send notes of these conversations to an Alabama scholarly journal, she challenged him to write a book instead. She then helped him to collect material he would use in the resultant Stars Fell on Alabama (New York, 1934), in which he fictionalized her as “Mary Louise.” An unexpected nationwide best seller, the book launched him on a successful literary career.

The Great Depression deprived the Tartt family of its land and financial resources. When Ruby’s mother and father died, she had to sell the family house and move to more modest quarters. Pratt Tartt’s health had failed and he was unable to work and Ruby, who had never previously given a thought to money, found herself middle aged, in debt, and with no income. In 1935 she took a job with a WPA sewing project, a form of public assistance. The following year, while at work sewing, she was told that the chair of the WPA Writers’ Project in Alabama, Myrtle Miles, was on the phone and wanted to speak to her. With characteristic self-deprecation, Ruby recalled how she rushed to phone:

I grabbed the receiver only to hear Myrtle Miles say, “Mrs. Tartt, you have been appointed chairman of the Writers Project of Sumter County” . . . . I quickly said, “I can’t write a correct sentence. I can’t spell cat. I simply can’t accept it.” Her comforting words were, “You may never have to write a sentence. Your first assignment is to send in, Monday, eight full-length spirituals.” I knew how little she knew of the time it would take to get the verses to eight songs. I told her spirituals didn’t thrive around the courthouse square, that I might drive all day in the country and never find one complete song. One person would know one verse, one another, and on. She insisted, and so I wrote her a letter about the songs, sending in some that I knew, avoiding of course “Swing Low Sweet Chariot,” which was about the only one she had ever heard. My letters had to be turned in to John Lomax in Washington, our greatest authority on folk songs. His reply was, “May I come at once to see you with my recorder. I am not familiar with any song you have sent in. Your area is rich in folk music.” And that was the beginning of my collecting hundreds of songs for the Library of Congress (quoted in Toting the Lead Row, p. 13).

John A. Lomax had become the National Advisor on Folklore to the WPA Writers Project, for which he had set up a list of questions and guidelines. It was a position he held for one year, having taken it with the proviso that he also be allowed to continue traveling and recording for the Library of Congress Archive of Folksong. Now he and his wife, Ruby Terrill Lomax, embarked on the first of several collecting expeditions in Sumter County, hosted, guided, and assisted by Ruby Tartt.

Trusted and esteemed by the African-American community, to the extent of being invited to offer funeral orations in their churches, Mrs. Tartt brought John A Lomax and his wife to the people, their churches, their funerals, even into their homes, introducing the them to local black singers and storytellers who might otherwise have been reticent about meeting, talking with, and singing for white strangers. The Lomaxes and Mrs. Tartt became lifelong correspondents and friends, and they returned in 1940 and 1941 to collect additional material. The long-established relations of friendship and respect between Mrs. Tartt and the black residents of Livingston and environs (and by extension between them and the Lomaxes) generated a treasure of priceless folk culture — exemplified by the songs and voices of Doc Reed, Vera Hall, Rich Amerson, and Earthy Ann Coleman — now preserved in the Library of Congress.

When Mrs. Tartt’s WPA project ended in 1942, straitening her finances, John A. Lomax urged her to publish some of her stories, but she was reluctant, deprecating herself as merely a conduit for the words of others. Lomax himself then submitted three of them to The Southwest Review, where they appeared in 1944. They were reprinted in Martha Foley’s Best American Short Stories of 1945. Harold Botkin’s acclaimed anthology, Lay This Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery, based on material from the Writers’ Project and published in 1945, opened with two of her pieces, causing her to exclaim that she was pleased to be “toting the lead row.” Yet, despite these successes, Mrs. Tartt remained diffident. Try as he might, Lomax could not convince her to write about Doc Reed, for example, whom both of them deeply admired. Injured by falling furniture from a tornado in 1945, she did concentrate on her writing, but only until her painting arm recovered.

As the outstanding interviewer and fieldworker for the WPA Writers’ Project, Mrs. Tartt made an invaluable contribution to the literature of American minorities. Some her interviews, as well as biographical details of her life, are available in accessible form in Virginia Pounds Brown and Laurella Owens’ slim volume, Toting the Lead Row: Ruby Pickens Tartt, Alabama Folklorist, 1981. Other recent collections of her work are:“Honey in the Rock”: The Ruby Pickens Tartt Collection of Religious Folk Songs from Sumter County, edited by Jack and Olivia Solomon (Mercer, GA: Mercer University Press, 1991); Dim Roads and Dark Nights: The Collected Folklore of Ruby Pickens Tartt, edited by Alan Brown (Livingston Press, 1993); and Gabriel Blow Sof: Sumter County, Alabama, Slave Narratives, edited by Alan Brown and David Taylor(Livingston Press, 1997).

From 1940 to 1964, Mrs. Tartt was County Librarian, then director for many years of the Sumter County Public Library in Livingston. “For me,” she said, “nothing is more rewarding than to bring good books and children together” (Toting the Lead Row, p. 53). It was renamed the Ruby Pickens Tartt Public Library in 1975 in recognition of her encouragement of young people to read and appreciate good literature. In 1950, she assisted Harold Courlander, who would write a book about Livingston’s Rich Amerson, Big Old World of Richard Creeks (Philadelphia: Chilton Book Company, 1962), and would later use much of the material he had collected in Sumter County in his Negro Folk Music U.S.A. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1963).She also helped Byron Arnold for his collection, Folksongs of Alabama (University of Alabama Press, 1950).

In 1961 the Montgomery Museum of Art held an exhibit of Mrs. Tartt’s artwork. She continued to draw and paint even into her 90s when, her hands too palsied to hold a brush, she used her fingers to lay on the paint. In the Sumter County Nursing Home in York, where she spent her last years, she continued to write down unfamiliar songs sung to her by the staff. On the occasion of her 94th birthday, she was wheeled through an exhibit of over one hundred of her artworks, brought from all over the Black Belt: cross-stitched samplers, drawings, sketches, paintings of bird dogs, churches, farmers and housewives, steamboats, portraits, and still lifes. Ten months later, Mrs. Tartt died on November 29, 1974. Her longtime friend Doc Reed sang “Steal Away, Steal Away Home” at her funeral. She was buried in the still segregated Myrtlewood Cemetery overlooking the Sucarnochee River, in Livingston.

In 1977, on the occasion of Ruby Pickens Tartt’s posthumous induction into the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame, Alan Lomax wrote:

Without her, a generation of the black geniuses who have made life in this country so much more livable and more beautiful by their wit and by their music would have been lost to us. In the stories that she wrote about them, in the interviews that she had with them, in the recordings that she helped my father and others make of them, Miss Ruby made certain that blacks of Alabama would have a just memorial.

Her published and unpublished manuscripts were given to Livingston University. The collection contains over 5,000 manuscripts of folklore and local history, including a large number of previously uncollected African-American songs, tales, and anecdotes. Her correspondence with John A. and Ruby Terrill Lomax is housed at the University of Texas, and there is further material at the Library of Congress.

John A. Lomax’s memoir, Adventures of a Ballad Hunter (1947), contains a chapter, “Alabama Red Land,” about Livingston and its denizens. The first half of Alan Lomax’s The Rainbow Sign: a Southern Documentary (1959) is based on interviews by Elizabeth Harold Lomax of Vera Hall, to whom they were introduced by Mrs. Tartt. His 1960 Folksongs of North America in the English Language includes the following songs collected in Sumter Country: “Knock John Booker,” as sung by Harriet McClintock (p. 497); “All for the Men,” as sung by Ruby Pickens Tartt (p. 499); “Ridin’ in a Buggy,” as sung by Vera Hall and Rich Amerson (pp. 535–36); and “Another Man Done Gone,” as sung by Vera Hall and Rich Amerson (pp. 539, 521–22). Recordings made by John A. and Ruby Terrill Lomax, assisted by Ruby Pickens Tartt, can be heard on Alabama: from Lullabies to Blues, with notes by Jerrilyn McGregory, Ph. D., in Rounder Records’ Deep River of Song series, edited by David Evans, (CD 11661-1829-2 in Rounder’s Alan Lomax Collection).

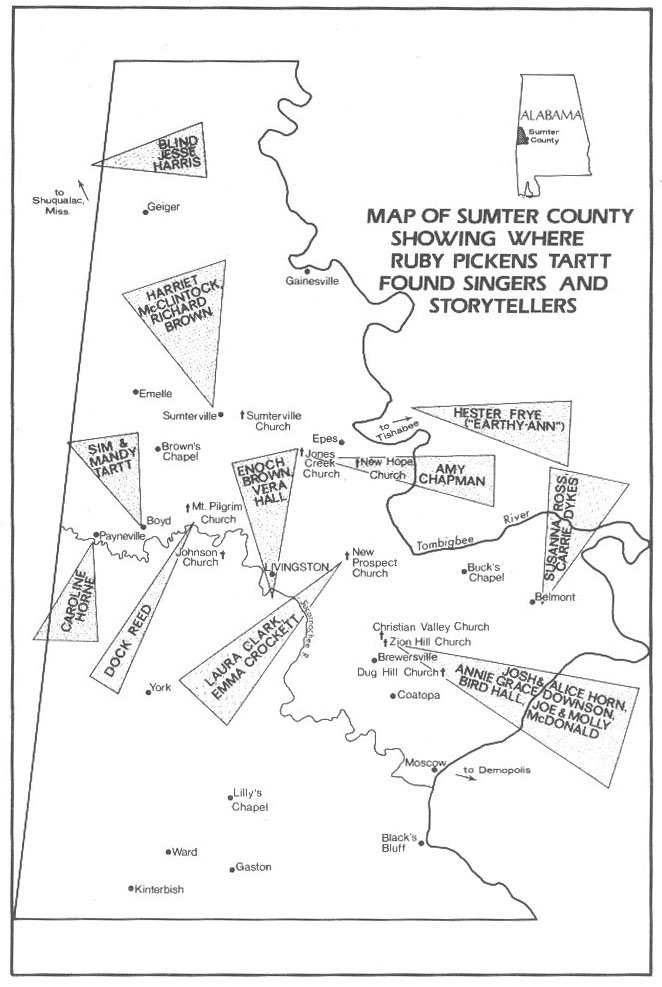

Map from Toting the Lead Row: Ruby Pickens Tartt, Alabama Folklorist by Virginia Pounds Brown and Laurella Owens, University of Alabama Press, 1981. Used by permission.