What Alan Lomax meant to me and this world

by Stetson Kennedy

When Alan Lomax, 87, passed away on July 18 near Tarpon Springs, where he had been struggling for nearly a decade to overcome a stroke, we not only lost a National Treasure (he was so designated recently along with Colin Powell), but an international one as well. Great is the loss, but greater still is the legacy.

Treasure though he was, there may be some out there who know not his name — another case of a maestro being out-shined by his protégés. Suffice it to say that it was Alan who gave us such luminaries as Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and Leadbelly, who each in turn gave us "This Land Is Your Land," "There's a Better Way on the Way," and "Goodnight Irene."

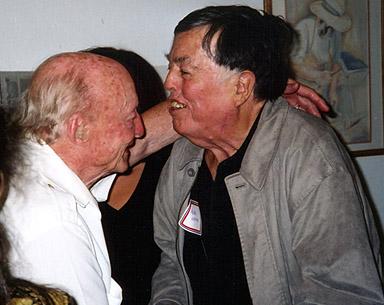

Stetson Kennedy and Alan Lomax, c. 2000

Who was he beyond that? None other than the world's foremost folk musicologist, whose clarion call and heroic example sparked a renaissance that rescued traditional folk cultures from being buried alive in a homogenized mudslide of "modernity."

To catalogue how he succeeded in doing this will require an encyclopedic biography. Pending that, let me commend to you Jon Pareles' superb obituary in the July 20 issue of the New York Times. Beyond that, there are Alan's monumental works cited therein. My purpose here is to put into the record a little something of what he meant to me. It was my great privilege to have Alan as a lifelong friend, and to hoe parallel rows, oft-times converging, tilling the fields of folk culture.

It all began in the mid-thirties, when I saw in the Jacksonville paper a photo of Alan's father John, a pioneer folksong hunter, chomping on a stubby cigar, who was passing through town after a recording session at Raiford. Young Alan often went along with his father, helping tote the 500-pound recording machine on loan from the Library of Congress. Where there was no electricity — as out on the railroad tracks and deep in turpentine camps — they also had to carry a couple of automobile batteries.

During those years father and son bagged more than 3,000 songs, and bestowed them upon the Library of Congress. Then and there they proceeded to set up an Archive of American Folksong (which flourishes to this day as the American Folklife Center).

In 1937, at the age of 21, I was put in charge of the Florida Writers Project folklore collecting, using that same infernal machine the Lomaxes had used. With Botkin in the national office, and the Lomaxes at the Library of Congress, we were all as excited as a bunch of kids on a treasure hunt.

A year later, in 1938, Florida's own African-American anthropologist, Zora Neale Hurston, who already had two books under her belt, signed onto the Florida project as a "junior interviewer" at $37.50 every two weeks, with me as her nominal Boss.

Alan had teamed up with Zora earlier, in 1935, on a recording expedition which began in her hometown of Eatonville. After the "mixed couple" had gotten some dirty looks from rednecks driving through all-black Eatonville, Zora insisted upon painting Alan black. After that, she led him through the Everglades and then up to the Georgia Sea Islands.

"In the field, Zora was absolutely magnificent!" Alan recalled to me recently. "She would honey-up the men so they wouldn't ask for money, and sometimes she honeyed them up so good she had to jump into that beat-up Chevy of hers, and flee for her life."

When my first book "Palmetto Country" appeared in 1942 (incorporating a deal of WPA material) Alan got hold of a copy and paid me the high compliment of saying, "I very much doubt that a better book about Florida folklife will ever be written."

He passed it on to Woody Guthrie, who was so enthused he wrote me a long fan letter (now in the forefront of the current edition), in which he asks me to send him some songs "of the kind that make Senators' wives faint when they hear them."

Woody went on to tell me not to be surprised if some day he came ambling up to my Fruit Cove abode Beluthahatchee (black Seminole, for "land where all unpleasantness is forgiven and forgotten") and sing me a few songs of his own.

He did exactly that, many times, and actually wrote his book "Seeds of Man" at Beluthahatchee. So I have Alan to thank for Woody, too.

During World War II Alan did a series for CBS titled “Transatlantic Call — People to People,” in which American and British townfolk took turns telling one another what they were doing to help win the war against the Axis. When it came time to do Key West and Tampa, Alan called me in as consultant. It was my first person-to-person working relationship with him. Although he was only one year my senior, he always pulled rank, but I never minded, because he was entitled.

After the war, when my "Southern Exposure" was published in 1946, I moved to New York as a base for speaking out against the Klan. There, in his Village apartment, I found Alan presiding over the folk renaissance he had sparked, MC-ing all sorts of hootenannies, indoors and out, featuring Woody, Seeger, Leadbelly, et al. In time I was invited to serve on the board of People's Songs, together with Alan and Botkin.

The frequent weekend parties at the Lomaxes were fabulous, betimes beginning on Friday after work, and continuing until time to go to work Monday morning. All of the above and many more (such as Sandburg, reading his poems) gathered there, and I often did the cooking, such as porkchops CIA, so-named after the operative I conned into giving me the recipe.

Almost nobody knows it, but northeast Florida came close to becoming home for Alan and his computerized world's greatest private folk music collection. It was in l998 that he planned he pull up stakes at Columbia University, where he had been based for 27 years, and return to his native Southland. He chose not Texas, where he was born, but Jacksonville, to seek a berth at UNF, and St. Augustine to look for a traditional Old South home.

With the help of Erick Dittus and other's at the mayor's office, and Dr. George Bedell (former chancellor of the Florida Board of Regents), we tried mightily to promote a residency for Alan at UNF. An interview was arranged with Ira Koger, in the hope that he might be inclined to fund a chair. Alan sang for him, but it was soon apparent that jazz, not folk, was Koger's thing. So they gave each other a bear hug, and parted with no hard feelings.

An important component of Alan's dream of relocating in northeast Florida was a sailboat, for island-hopping (and no doubt song-hunting) in the Caribbean.

But the window of opportunity — for him and for us — never opened, and in 1989 Alan simply moved his Global Jukebox downtown to Hunter College in New York.

He was still going strong when felled by not just one but two strokes in 1995. Since then, he had been convalescing at the home of his daughter Anna Lomax Chairetakis in Tarpon Springs. Following in her father's and grandfather's footsteps, Anna is a distinguished folklorist in her own right, having made notable collections in Italy and Spain. Ever since his stroke, she has been editing a 100-CD series drawn from his collection of folk music of the world.

Some interviewer in recent times reported that as he aged Alan "had become something of a curmudgeon." But I have news for her: Alan emerged from the womb as something of a curmudgeon. But his targets almost always had it coming to them — like the international academic congress of folklorists who he castigated for their ivory tower disdain for real folk. The academes literally threw him out.

I once asked him why he had not bothered to get a Ph.D. himself, and he responded, with a twinkle in his eye and all the modesty in the world, "Who would judge me?"

So much for what Alan Lomax meant to me personally. I loved the guy, who was actually a messiah who not only preached the gospel of faith in folks, but practiced it in infinite ways.

As with those precious few others who have changed human lives for the better — such as Guttenberg, Leeuwenhook, Curie, Einstein, Edison, John Brown, and MLK — Alan Lomax's truth will not be interred with his bones, but will go marching on to enrich the lives of future generations, for as long as there are folks on earth.

Used by permission of the author.